Remembering Daddy Flo

It has been seven years since I last heard my father’s echoing laughter. The warmth in his voice now rests only in memory. Jamaica Kincaid once wrote that losing a parent is like losing the shield between you and eternity. I did not understand this until the day my father died. That day, we grew up overnight and stepped into roles far heavier than our shoulders were ready to bear.

Conversations shifted. Uncles who once gave us money for pouring water as they washed their hands were now asking tough questions, “Where shall we bury him? In which attire? Select the coffin and buy food for the mourners.” Suddenly, decisions previously solely taken by our father became ours. The fight for land justice which our father outspokenly stood for, also inherently became ours. My brother Hannington, the only son, had it worse.

We selected a blue suit with the support of our cousins. We imagined that our father wanted to be very smart when he met Jesus. He was dressed in blue, his favourite colour of all time. He wore blue shirts, wrote in blue ink and drove blue cars with cranky engines.

For 34 years, I had known my father. But on November 20, 2018, when he transitioned, I began an unfamiliar life. A life without the shield of his love, protection and wisdom. He was my confidant and now when I look back, he was my guiding star and voice of reason. He called me Flozensi or Flo but towards the end of his life, he respectfully called me Mama Gabbie. He named me Florence after his sister Florence Robinah, and I guess it made him proud when people called him Daddy Flo. My mother recalls the day I was born and the thrill of becoming parents who were young and deeply in love with more love than means and the hospital bill was settled with contributions from family members. Now Daddy Flo, my shield of 34 years was gone, without him life felt frightening, hollow and unfamiliar.

What began as afternoon chills slowly revealed itself as something deeper. Daddy Flo rarely fell sick. He had a phobia for hospitals and medication. He believed soup was the cure for everything, “omuchuzi guwonya,” he would tease as he emptied bowls of chicken broth my mother lovingly prepared.

After a misdiagnosis of ulcers and appendicitis, a second doctor revealed a tumor on his liver and recommended a biopsy to confirm whether it was cancerous or not. L i v e r??? Ekibumba? shaken by the word “liver” he said “Kitange yafa kibumba,” remembering his own father’s death from liver disease in December 1964. Despite all pleas, Daddy Flo adamantly refused to have a biopsy done. He described the biopsy apparatus and equated them to “olukato’, the long needle we used to stich sacks of coffee.

So, he lived the next seven months quietly going on with his work at Kayunga and doing the things he loved; attending weddings, tending to his cows, and, in hindsight putting his affairs in order. When his strength waned, he masked it with humour and music.

I remember him singing to Jim Reeves, Kenny Rogers, Maddox, and Henry Tigan. He kept a collection of music on C.D’s and when things got tough between my mother and him, he played music to win her back. My mother used lusilika (silent treatment) as a weapon of defense. Her silence disturbed my father, and he would cajole her with music. “You can run; you can hide but you cannot escape my love.” He played it repeatedly as Mum furiously banged saucepans in her kitchen outside and soon her anger dissipated, and she would serve him her signature “summersaulting” omelet. My mother had a way of tossing the pan and omelet would do a showy summersaulting dance before it landed back into the pan. My father loved her cooking and then he complemented her “Mummy Flo, wabula ofumba ejji” then the lusilika would end, and peace would prevail with more country music. “You got me, I got you, we got love.”, “owange Namagembe nkwagala nnyo tondeka nga wo.”

As the liver disease worsened, he lost so much weight. Worried, my mother boosted his immunity with GNLD supplements and herbal medicines. He took the supplements until he called me one day.

Tell Mummy to stop giving me her medicine

I am tired of medicine.

One Sunday, we went home for lunch as we usually did. This time, I was accompanied by my childhood friend Ethel. Her mother was undergoing chemotherapy at the time. I had hoped that Ethel would encourage him to do the test and truly she did except the conversation ended in a political debate. I realized he was trying to distract us from his pain. He was silencing us from talking about his illness which had become a huge elephant in the room.

In the evening, he asked us to drive him to see family in Kireka, but my mother pulled me aside and whispered,

“Mumutwale mudwaliro.” (take him to hospital)

“He is holding it strongly for you.”

“In the night, he falls really sick.”

I listened to my mother and booked an appointment immediately. By 9:00 am the following morning we were back at Nakasero Hospital. He was very cooperative this time and finally agreed to the biopsy.

The results confirmed cancer. The diagnosis broke him. It broke all of us. We were counselled by the doctors to support him.

The events that followed unraveled rapidly. Arrangements were made for an emergency surgery in India. A medical evacuation to India meant that assets had to be liquidated as he did not have medical insurance even after 22 years of public service! My mother suggested that part of the land be sold to raise the wherewithal, a plan that died on arrival. He refused to sell his father’s land, land he had protected all his life and instead said we sell his beloved blue Ipsum. The car that he drove to many weddings, visitation days, the airport and carried food for the coveted cows ; Donna (named after Donald Trump), Nassolo, and Tusubira to mention but a few.

In the end, nothing was sold. Family and friends carried us through. In that moment, I learned that many of us are only one illness away from financial ruin, and that where health systems fail, community becomes our insurance. We also took loans to finance the operation. At last India was sorted, oh so we thought!

Dad and Mum’s passports had expired and needed immediate replacement. Any delays would affect the schedule. The doctor at Nakasero hospital wrote a recommendation letter to hasten the process. In that moment I also learnt that your countrymen are yours until they are not. Some folks turned our vulnerability into cash cows. Give us “something” if you want the passport quick. Desperate calls were made to people who knew people. After days of standing in the tent, finally the passports were released.

The flight to India was the longest as Hannington and Mum Narrated. Dad’s pain outgrew all the strong medication. The air conditioning made it worse. Finally, they were received by a medical team in India.

India offered hope at first with advanced machines and professional doctors but the language barrier with the nurses and constant miscommunication made the journey difficult. After days of tests, the final verdict came, the cancer had spread too far. Surgery was no longer possible. The doctors advised us to return him home immediately for palliative care. The news was overwhelming. Hannington and Mum were cryinguncontrollably, which made travel arrangements even harder. How were we going to book return flights without alarming Dad?

I spoke to Dad briefly as he had become withdrawn, refused to eat or talk to anyone. He was worried, yet there was nothing we could do. They were so desperate in a foreign land. What would they do if Dad were to die in India, so far from home?

“We love you”, he said and ended the call abruptly.

Happy, Noela, Irene and I tracked that Emirates flight home minute by minute, praying he was still alive midair. When they finally landed, he looked frail, his warm eyes down cast, he had lost the hope that India once promised. His hands were colder than they had previously been when we held hands to pray with Pastor Chemonges. “wakili okufila e Uganda… e Buyindi ani akumanyi?” he whispered. At least he would die at home in Uganda.

His final days at Nakasero were a mixture of confusion and tenderness. Doctors contradicted each other. Doctor X said ‘do not give him sugar,’ Doctor Y said ‘give him everything he wishes’ and issued a permission slip. Doctor Y said let him rest, Doctor Z said take him home, there is nothing more we can do. Doctors were changed with every shift; it appears that none of them wanted him to die during their shift. They did not counsel us but instead talked amongst themselves “he doesn’t have long”. Pain medications were given, and his heart was monitored in intervals. The hospital was getting concerned as visitors flocked to our room. They came to say goodbye.

The waiting was full of anxiety and uncertainty. My father was dying but it was not time to cry. His friends Engineer Kirinnya, Mr. Musisi and his work family at Kayunga surrounded his bed. He spoke longest with Engineer Kirinnya, the one who taught him new dance strokes. I remember how hard they danced at Uncle Ssembatya’s wedding. Paka last as Engineer loved to say. Engineer listened intently, and only then did we learn how long he had suffered in silence. I will pause here to say that sometimes it becomes hard for parents to share their vulnerabilities. We need to watch their actions than their words. Fathers are strong for everybody but who is strong for them?

For the rest of the days, Uncle Katwele kept us awake with humorous stories. My cousins Joan and Josephine rubbed Dad’s feet while my Auntie Robina led hymns. Obude buzibwe enjuba egenze, a childhood hymn their mother, Jajja Nnalongo had taught them. Jajja Nnalongo did not come to hospital due to advanced dementia which she would eventually succumb to. She couldn’t remember anyone save for Uncle Isaac. ‘Ondabila Nnalongo, Dad said to Auntie Robina in a rather desperate and longing tone. We said all the prayers our hearts knew and in times of despair, sang all the hymns Dad loved. Songs became the prayers of our hearts.

Dad’s cravings became unpredictable, he wanted yams ‘obukupa’, oats, butunda, and milk and then he didn’t want anything. His voice grew softer, his breath shallower and his throat clogged. Yet his mind remained clear.

On Monday, my father began preparing himself for his final journey.

“Comb my hair,” he requested.

I brushed his hair gently as it had coiled like Kaweke and grayed more than the last time I dyed it.

“Trim my nails,” he said, as though tidying himself for an appointment. I trimmed the finger nails, but the toes were swollen from end stage Edema.

Then he asked for deodorant.

“Dad, where are you going?” I teased gently.

He only smiled.

That evening, Polly and I knelt besides his bed before we returned home to check on the children whom we had left with Brenda and Primus. He held my hand longer than usual.

Mundabila abaana,

“Bye,” he whispered, simple and in hindsight final.

That night, the death rattle began. He hallucinated, called for my mother, pressed her hand to his cheek, then dismissed everyone else“Abana bavewo.” (Even in death, he was still protective of his children).

Although he loved English very much, collecting new words and teaching us vocabulary from newspaper clippings, he died in Luganda, the language of his mother and father.

“Mundeke mpumule.” Let me rest.

When I touched his cold face in the mortuary, Kincaid’s words made meaning. My shield between me and eternity was gone! My father, who had protected me since as a child born during the 1980 war and life’s unending challenges, had slept a forever sleep. I remained in the mortuary with Steve (Love after fori) and my good friend Isaac Teko as the rest of family left. I touched his hair and felt the same way as the night before. Dad, why didn’t you wait for me, I had gone to see the children. Finally, I whispered to him ‘goodbye’.

In the years that followed, grief became a companion I did not invite but learned to live with. I searched for my father in his journals, volumes filled with quotes, reflections, and neatly written words he had collected over the years. He wrote letters, some of which he never sent to intended recipients, documented the births of his cows, and kept files and school records from decades ago. His left handwriting remained pristine like the way he tucked in his shirts. I also read the memoir which he wrote in part and promised myself that I would complete it but writing about my father became more difficult than I had ever imagined. (Special request, if you know a publisher who would be willing to work with me, I am ready to engage).

My mother became someone new, fragile with sorrow, avoiding their house because every corner reminded her of him. His clothes, photos and gumboots became a painful memory. My siblings grieved differently, some silently, Happy writing letters to him, some trying to distract themselves with work. Noela applied for a Masters degree. Hannington tried to fill in shoes too big for him and when the cows started dying, he felt helpless. We held on to each other, as our cousin Simon advised, stick together, Mugume.

One night, on my way to check on Polly, I found a drunken man collapsed in the road. I burst into tears of anger, grief, disbelief tangled together. Why did God take my sober father, who longed to live, and leave this idiot who was trying to kill himself? Grief can be irrational like that, wild and unforgiving.

But as the years passed, grief softened. It became a teacher rather than a tormentor.

It reminded me that life is fleeting and fragile. It taught me to create memories with family (photos of all the moments we had, kept me warm), to hold my people close, laugh loudly, love them deeply, and most importantly to never take time for granted. I had taken it for granted that Daddy Flo would be with us forever.

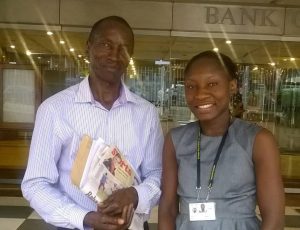

Today, when I look back, I am grateful for the memories we made: his visits at my workplace with bananas, the Friday outings to Amagara restaurant when he could never eat without packing for Mummy, the way he held my hand when we crossed roads, the lullaby of baba black sheep which he sang to us and our children, Gabbie and Kemmie and Milan. How early he had driven to pray with me before any flight. The sweet day in January 2017 when shifted to our first home, the home in which we would eventually nurse him. The good cheer and assurance he always gave me.

It has been Seven (7) years since all that love was silenced.

Life is as Matthew West sings in his song Wonderful life; broken and beautiful, gone mad and magical, awfully, wonderful!

We miss you, Daddy Flo!

Words are my precious gift to you.

Thank you for being part of my story.

© 2025 Florence Katono . All Rights Reserved.